The American Calvary, overwhelmingly favored to win the battle, threatened to cut a certain body part off of all captured Indian soldiers so that they could never fight again. The Indians won in a major upset and waved the body part in question at the Calvary in defiance. What was this body part?

The resistance, known as the Winnebago War of 1827 was led by chief Red Bird. Using this threat of having the body part cut off by the American Calvary to his advantage chief Red Bird convinced the Brothertown Indian tribe, the Ho-Chunk Indian tribe and many other smaller Indian tribes to unite in battle. When the American Calvary in their schooners encountered the united Indian armada they immediately retreated. With the armada in pursuit the Calvary retreated through Oshkosh, Winneconne and headed up the Wolf River to Fremont.

With superior knowledge of the local area chief Red Bird took a select group of warriors and headed on shore to a high bank just beyond Fremont. When the Calvary arrived they found the deep keels on their schooners were more then what could clear the shallow water at this spot of the river. At this point the Calvary could continue no more and were easy targets for the Indians perched high above on the river banks. This shallow wide area, later named “Red Banks” in the chiefs honor was not dredged until almost 100 years later.

With the Calvary unable to go forward they reversed course back to Fremont until they reached the awaiting Indian warrior armada. Scared and facing certain death the Calvary set fire to their own vessels and retreated up the west river banks slipping away from the battle. This very spot became known as “Slip knot.” Defeated and scared the American Calvary ran and did not stop until they reached Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin.

Victorious in battle chief Red Bird ordered the Indian warriors to wave the very body part that the Calvary had so arrogantly threatened to cut off. The body part the American Calvary threatened to cut off of the Indian warriors was the middle finger, without which it is impossible to draw the renowned longbow, favored by the Indians. The act of drawing this long stiff bow made from wood from the yew tree was known as "plucking yew." The victorious Indian warriors shouted to the retreating American Calvary as they ran up the river banks "See, we can still pluck yew! PLUCK YEW!"

Embarrassed by the humiliating defeat President John Quincy Adams, in Nov. 1828 ordered all official records of the battle to be rewritten in favor of a union victory however the story of the battle of Winnebago continues by being passed on generation to generation.

Over the years some 'folk etymologies' have grown up around this symbolic gesture. Since 'pluck yew' is rather difficult to say (like "mother plucker", which is who you had to go to for the feathers used on the arrows), the difficult consonant cluster at the beginning has gradually changed to a labiodental’s fricative 'f', and thus the words often used in conjunction with the defiant gesture are mistakenly thought to have something to do with an intimate encounter. In honor of the victory lead by Red Bird, the Indian chief, the symbolic gesture has become known as "giving the bird".

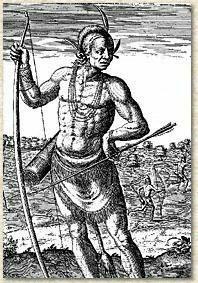

Today a statue displayed at High Cliff state park commemorates the battle between the Indians and the Americans. To honor this revered leader, a 12 foot statue was erected in High Cliff State Park. Historical revisionists and citizens for decency have forced the officials to have the statue modified from its original historically accurate portrayal as seen in this original photo below to adding an extended pointer, ring and pinky finger next to the middle finger. However if you visit this statue today at High Cliff state park on the north east corner of Lake Winnebago, Wisconsin and you get on someone’s shoulders to take a close look you can see the other fingers are not a perfect match.

The original Statue of chief Red Bird at at High Cliff state park

You can read more about this infamous chief at and this historic battle by visiting the High Cliff General Store Museum. The High Cliff General Store Museum shares the history of the park in one of the original buildings from Sherwood's past. Additionally, visitors can purchase ice cream, candy and other items while examining the items in the museum. The High Cliff General Store Museum is open Friday through Sunday from Memorial Day through Labor Day from noon to 5 p.m.

Native American history is abundant in Calumet County. There are several memorials, preserved burial grounds, and effigy mounds to go back in time and tap one’s desire to experience and learn more. From the Brothertown Indian Memorial at the intersection of Highways 151 and 55, to the Chief Red Bird Memorial in High Cliff State Park, the historic gems you will discover will awe you.

History is not lost on today's residents of Calumet County. Indeed, it is celebrated to this day by keeping the historic traditions alive, specifically by the fisherman of Lake Winnebago.

Now that you know the history you can do your part to keep the storied tradition alive and help repair the rift that divides between cruisers and fishermen through this day.

When you are out on your cruiser and you come across an anchored fisherman rather then avoiding their general vicinity alter your course to take you close to their side. As you pass them hold up your right arm with your middle finger extended and shout “Pluck yew!” If they return with the same geniture and reply “Pluck you too!” you can be proud that you are doing your part to repair this long standing divide between fishermen and cruisers.

2 comments:

Thank god some historians are still sticking to the facts, or we would lose priceless stories like these, forever.

Post a Comment